Editor’s Note: This speech was originally delivered at the 2015 Florida League of the South Conference.

Introduction

Why is there a South? What is this place we call the South? What makes it different from other parts of the United States?

Many years ago, the Alabama writer Clarence Cason wrote that the South was “self-conscious enough and sufficiently insulated to be thought of as a separate province.” Echoing the same theme, W.J. Cash called the South, “not quite a nation within a nation, but the next thing to it.” In his book The American Dilemma, the Swedish sociologist Gunnar Myrdal agreed with Cason and Cash that the South was “a nation within a nation.” The Southern historian Ulrich B. Phillips once quipped about a ferryman calling the north bank of the Ohio River “the American shore.”

Surely, there is something to this long persisting notion that the South is a separate and distinct place from the rest of the United States and that the Southerners who live here are a separate and distinct people, who are unlike other Americans in some critical way. Southern writers, political theorists and historians have been defining the South for generations. The Southern people are studied by academics both at home and abroad more intensely than ever before. Among other universities, the University of Mississippi even offers a master’s degree in the subject.

I’m going to argue here that the land made the Southern people, and the Southern people in turn shaped the land. The South is a bioregion. Think of the South as being like a bottle of fine aged wine. The bottle provides the shape while the contents provide the taste.

The Soil

Climate Zones of the Continental United States

Long before humans arrived in the South, there was just the land. Like China, the vast majority of the American South lies within a “humid subtropical climate” zone. Everyone who has lived in or traveled through the South is familiar with our subtropical climate which is not found elsewhere in the United States. We have long, hot and humid summers and short, mild to cool winters.

It’s usually bright and sunny in the South. The air is sweet and sultry. Because of the milder temperatures, we have a longer growing season and fewer winter freezes than the North. It doesn’t snow as much here as it does in the North and our skies are far less cloudy and overcast than in Britain.

Physical Divisions of the United States

Geologically speaking, the majority of the American South is dominated by the Gulf Coastal Plain and the Atlantic Coastal Plain, which are low lying areas that were underneath the sea for millions of years. The bedrock here is deeply covered with sediment and the soil is more sandy than the continental soil in the Midwest. The rivers that flow through this region are slower because of the low elevation.

The Upper South is dominated by highlands: in the west, the Ozarks and Ouachita Mountains in Missouri, Arkansas, and Oklahoma; in the center, the Interior Low Plateau in Kentucky and Middle Tennessee; and in the east, the Appalachian Mountains and the Cumberland/Allegheny Plateau.

The Piedmont lies between the Appalachian Mountains and the Atlantic Coastal Plain. The Atlantic Fall Line, which is where rapids begin and rivers typically cease to be navigable from the ocean, divides the Piedmont from the Atlantic Coastal Plain. This is the border of the ancient ocean and used to be the shoreline.

100th Meridian

The 100th meridian is the unofficial border between the American East and American West. West of the 100th meridian, the climate rapidly becomes arid and rainfall becomes scarce. This is also nature’s border between the Southeast and the Southwest.

America’s Rivers

There are more navigable river systems in the wet, humid, subtropical American South than anywhere else in the United States.

Great Plains

Along with the 100th meridian, the Great Plains which run through Texas and Oklahoma form the natural western border of the American South.

Black Belt Region

The Black Belt is a crescent shaped band of rich, dark topsoil that stretches from southern Virginia to eastern Texas. Until the march of the boll weevil across the Deep South between 1900 and 1920, it was the ideal soil for growing short staple cotton.

Coal Production, 1901

By 1901, coal mining had spread across Appalachia, but before the War Between the States, coal mining was concentrated in the anthracite fields of eastern Pennsylvania, which contain the highest quality coal in the United States.

Iron Regions, 1899

By 1899, iron ore was being mined in southern Appalachia around emerging cities like Birmingham and Chattanooga, but before the War Between the States, iron ore was mined primarily in Pennsylvania. Geologically speaking, the American South is simply inferior in iron ore to the North. Even today, 95 percent of America’s iron ore is mined in Michigan and Minnesota.

So what’s the point of all this?

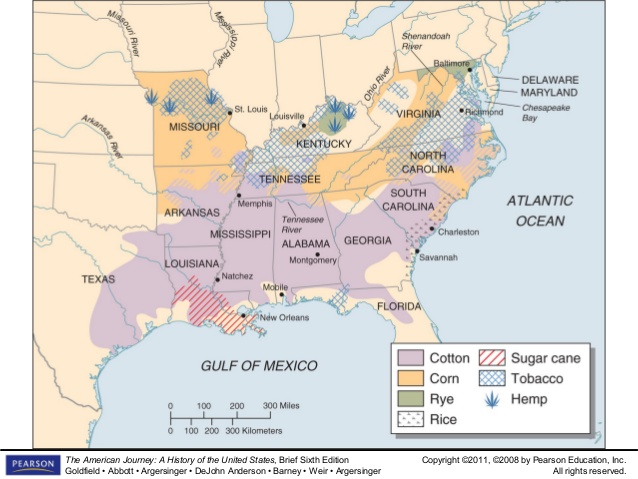

The point is that the climate and soil of the American South, the sum of our environment, set us down a different development path than the North. Among other things, it determined which crops were grown, where these crops were grown, who labored in the fields, where cities were built, the size and scale of plantations, where the rich and the poor settled, whether wealth was concentrated or dispersed, the racial composition of the population, why agriculture was favored over manufacturing and commerce, why the South had less need for internal improvements, trade policy and so forth.

To a large extent, the land itself determined the nature of our culture and economy, and by extension the course of our history. We needed fewer railroads because we had more navigable rivers. Although we had more navigable rivers, our slower rivers were less suited for textile mills. It made more sense for us to export cotton than to build factories. Climate and soil imposed hard limits on where cotton and tobacco could be profitably grown – the South’s subtropical climate all but ruled out sugarcane, except in southern Louisiana – and where Southern civilization could spread in North America.

The South is a bioregion. It has a certain unity about it that has given us borders, molded the people who live here and has given them fixed interests which are in some ways antagonistic to the rest of the United States. Even when there has been conflict within the South, such as the conflict within Appalachia during the War Between the States, this can be explained in terms of one ecoregion overlapping with another.

As the history of New France and New Spain show, that’s obviously not the whole story. Let’s take a look at the founding stock who settled the South and the ideas which they brought with them from the British Isles. It was the English, not the Spanish or the French, who ultimately established their dominance in this region and determined its destiny.

Settlement

British Origins

In the beginning, we were English and Christians, but our ancestors who founded and settled the Southern colonies weren’t any ordinary English Christians. The founding stock of the lowland South were disproportionately drawn from the South of England, the West Country, metropolitan London and other English cities like Bristol. The Scots-Irish who came later and settled Appalachia and the backcountry were drawn from the North of England, the Scottish borderlands, and Ulster in Ireland.

This is highly significant because the founders of Virginia and Carolina, whether rich or poor, were drawn from the “mainstream” of English society. They established the Anglican Church in all the Southern colonies except Maryland. They were commercially motivated. They were not religious fanatics who fled the Old World to create a religious utopia in the American wilderness. Instead, our ancestors were country gentlemen, soldiers, the adventurous sort, merchants, and poor indentured servants, or in the case of the Scots-Irish, refugees who were pushed out of their lands.

The key point here is that our real founders, unlike their counterparts in the Northern colonies, were not ideological. They were conservative in that they sought to reestablish familiar patterns of life.

British West Indies

Before we go any further, we have to stop and take a look at a long lost branch of our family tree, the British West Indies. The exact same people from England who settled the lowland South also settled the British West Indies. It was here in a true tropical environment, principally in Barbados and Jamaica, that “Southern civilization” flourished on an even grander scale than it ever did here.

Many of things we commonly associate with the South are exports from the British West Indies. Unfortunately, the 17th and 18th century Caribbean proved to be too sickly of an environment for our forebearers to demographically establish themselves there. They created slave societies, but failed to create settler societies.

Cultural Hearths

In Virginia and Carolina, our succeeded in creating settler societies. The humid subtropical climate of the South was better suited for White settlers and slave societies to flourish. The South was too far north though for sugarcane. As a result of this, Southern plantations and their slave labor force were smaller than their counterparts in the West Indies.

The founders of Virginia set out to recreate the country gentlemen society of the South and West of England from which they had came in the Tidewater region. Initially, they imported indentured servants to work as laborers on their tobacco farms – in a world of abundant land, labor was in scarce supply – so bonded labor was required to get the job done. By the late 17th century though, the English poor had better options at home. Ultimately, Virginians learned to cultivate both tobacco as an export crop and to import black slaves to work on their blossoming plantations from the Barbadians.

In South Carolina, the Barbadian influence was more clear cut. The founders of South Carolina were culture bearers from Barbados who had already spread their civilization across what became the British Caribbean. From the outset, they introduced the established West Indian model in South Carolina, with the full suite of slavery, white supremacy, the racial caste system, plantations, and export based cash crop agriculture that prevailed in the tropics, in this case, rice, indigo, and long staple cotton. The planters even built themselves a town, Charles Town, modeled on Bridgetown in Barbados.

In the early 18th century, the Scots-Irish arrived in America through Philadelphia and other Chesapeake ports, and began their epic migration out of Pennsylvania and down through the Great Valley into Appalachia and the Southern backcountry. The fiercely independent, warlike Scots-Irish carved themselves out a homeland on the frontier and yearned for nothing more than to be left alone to prosper.

Growth

Americans Spread West

By the mid-18th century, the first “South” had emerged out of the confluence of these three “cultural hearths”: Jamestown, Charleston, and Appalachia.

The introduction of black slavery, frontier warfare with Indian tribes, and the arrival of European minorities like Germans, Irish and French Huguenots that complicated the demographic profile of the colonies had also given rise to something new: White racial consciousness. After several generations in North America, Southern identity was English, Christian, White, and free.

The American Revolution replaced English with American. The course of the Revolution, the debates at the Constitutional Convention, and the onset of sectional conflict within the Union began to nurture a new identity: Southern.

As Americans spread west in the 19th century, Southern came into sharper and sharper focus as the conflict with the Yankee became more intense. Until the 1850s, Southerners had dominated the presidency, Congress, and the Supreme Court. Lulled into a false sense of security by decades of tranquility, Southerners hadn’t given much thought to the tension between Southern and American identity because Southerners up until that point had dominated and defined America.

Slave States vs. Free States

By the 1850s, the “irrepressible conflict” between the slave states and free states was underway, and American identity was polarizing into rival camps.

Led by Sen. John C. Calhoun, Southerners had nurtured their own political philosophy, the states rights theory of American government, which sees the Union as a voluntary compact of sovereign states created by mutual consent. This tradition was derived from Jeffersonianism, the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions of 1798, the Anti-Federalists, and John Randolph and the Tertium Quids. Since each state had separately ratified the Constitution, it follows that any state can withdraw from the Union.

In contrast, Northerners led by Sen. Daniel Webster argued in favor of an indestructible Union that preceded the Constitution and was created by the Declaration of Independence. Under this theory, the states had been created by Congress, and no state could unilaterally withdraw from the Union without the consent of Congress. This set up an irreconcilable conflict over what the US Constitution really meant.

The conflict with the Yankee raised deeper, more fundamental questions because the “freedom” that Americans had fought for in the American Revolution meant different things to different regional cultures. “Freedom” to the Scots-Irish had meant the “freedom” to be left alone and settle the trans-Appalachian West. “Freedom” to the lowland South had meant “independence” from Lord North’s consolidationist policies. It did not mean “freedom” or “equal rights” for Southern slaves. It was the British, not the Continental Army, who had fought to free the slaves. In fact, the Declaration of Independence had condemned King George III for the crime of inciting “domestic insurrections” among us.

Whereas Yankees had risen in revolt in the name of a few taxes on tea and stamps and the abstract universal rights of all mankind, Southerners revolted against King George III because, fundamentally, the Southern Founding Fathers felt we had been disrespected.

Southern Crops

By 1860, Texas and Arkansas had been added to the roster of slave states, and the Southeastern Indians had been relocated to Oklahoma. Southern slavery had reached its bioregional limits. There was still plenty of room for the Cotton Kingdom to grow, but in the future this growth would occur within existing states.

The balance of power within the Union was shifting toward the Free States with their booming population. The marginalization of the South within a Northern-dominated Union hostile to Southern interests was inevitable. Yankees would use the Union as their instrument to reduce to the South to the status of an internal colony with the Northeast reprising the metropolitan role of Great Britain.

Maturity

The Confederacy

That’s why we got out.

There were good reasons to stay put. Slavery would have lingered on for decades. Leaving the Union endangered slavery, but staying within the Union meant domination by a people with ideas and interests fundamentally antagonistic to our own.

Getting out of the Union was easier than constructing an enduring Southern Nationalism. The architects of the Confederacy were conservatives who were forced by public opinion into secession. They essentially copied the US Constitution out of fear that making bolder changes would divide the South in a military crisis. They even copied the US flag which they replaced with the Stars and Bars.

Southern was still too weak of a national identity to take such risks in the secession crisis. Southerners were just beginning to reflect on their ethnic and cultural origins like the Irish, Poles, and Italians in Europe. When the war came, we were still pondering our Norman and Cavalier origins and lacked the public schools to instill belief in a common ethnic identity in the minds of the masses.

War Between the States

During the course of the War Between the States, Southerners acquired our own flag, national anthem, and heroes. “The South” even acquired a proper name, “Dixie,” which was the land of “Southrons,” a term borrowed from Sir Walter Scott. These were all ingredients of a blossoming national identity.

Nothing stimulates the emergence of nations like an old fashioned bloodletting followed by a humiliating defeat and a brutal military occupation – just ask our next door neighbor, Mexico. The defeat that Mexico suffered in the Mexican War pales in comparison to the magnitude of the defeat of the Confederacy. Whereas Mexico lost half its territory, we lost our independence to the United States.

Nearly 1 out of 3 Southern White men lost their lives in the war. Countless more were maimed for life. The war wiped out $3 to $4 billion dollars in slave property. While Northern wealth grew by 50 percent during the 1860s, southern wealth declined by 60 percent. The numbers don’t do justice to the abyss of poverty in which the defeated South was hurled into during Reconstruction.

The war was followed by 12 years of carpetbagging and occupation and about 35 years in total before the South was fully “redeemed” and something resembling normalcy was restored when the Jim Crow system was created. Where the Confederate war effort hadn’t succeeded in unifying a separate and distinct Southern people, the Northern yoke of generations of suffering, poverty and oppression succeeded where our armies and political theorists had failed.

The Solid South

In the decades that followed, the South became an internal colony of the East and we chopped our own cotton and worked for the Northern banks, railroads, timber companies, textile mills, steel and mining corporations which plundered our natural resources as the fruits of their victory. We bought Northern manufactured goods at inflated prices while selling our cotton for nothing. We were taxed to pay for the pensions of the Union Army veterans who conquered us. Under this “New Birth of Freedom,” we borrowed money from Yankees to be crucified on their Cross of Gold.

Southerners found greater political unity as the one party “Solid South” which had never before existed. We raised monuments to the Confederate dead. In the years after the war (the defining event in our history), we became a “nation within a nation” with the custom of celebrating public holidays that commemorate a generation of men who died fighting against the United States.

The Jim Crow South

“Home rule” was the hard fought and long sought consolation prize for our second place finish in America’s “Civil War.”

Just as Alexander Stephens had described slavery as the “cornerstone” of the Confederacy, segregation emerged as the cornerstone of the Jim Crow South. Even though we had lost our independence, our money and a generation of our men their lives, we continued fighting into the 20th century for what the historian Ulrich B. Phillips labeled in 1929 the “cardinal test of a Southerner” and “The Central Theme of Southern History,” which is our “resolve indomitably maintained – that it shall be and remain a White Man’s Country.”

By the 1940s, Southern identity meant being White, Christian, Southern, and free. In his scathing 1941 book The Mind of the South, it is worth noting that it never occurred to W.J. Cash, who was an iconoclastic critic of the Old and New South, that the Southern mind meant anything other than the collective consciousness of the White South, 98 percent of whom believed in segregated schools in 1942. Such a statement today would probably be met with a mixture of befuddled shock and confusion and talking points about “Black Confederates.”

In The Mind of the South, Cash had written about the “Savage Ideal” and the “Proto-Dorian Bond” that he believed were at the heart of Southern culture, which were his terms for the bond that unified all Southern Whites, no matter their class, to maintain the racial caste system and suppress dissent by liberal Whites. In fact, Cash was right on this score. The White South had a long tradition of driving its own Uncle Toms into exile. A short list would include John G. Fee, the Grimké sisters, John Rankin, Hinton Helper, Walter Hines Page, William P. Trent, George Washington Cable and Erskine Caldwell.

Southern Crops, 1925

Between 1860 and 1890, the Cotton Kingdom nearly doubled in size, and it more than doubled in size again between 1890 and 1925.

The lyrics of Dixie begin with the line, “Oh, I wish I was in the land of cotton,” and that was never more true than it was in the 1920s, when sharecroppers chopped far more cotton than slaves ever did during the Confederacy. A century ago, the South was still an overwhelmingly rural and agricultural world.

This benighted land of boll weevils, kudzu, and pellagra was in a world of economic pain – in Dixie, there was never a Roaring Twenties, and Southerners had been mired in the “Great Depression” since 1865. Several generations of poverty had tied our people to the soil, but left them relatively homogeneous and rich in a folk culture that was rapidly disappearing in the modernizing North. Their closer ties to the land gave them close knit communities, stronger families and a sense of place around which they oriented their lives. Even the families who lived in our mill villages in the Piedmont or the company towns of Appalachia fondly remembered the sense of community of those days.

A major theme of the poets and writers of the “Southern Renaissance” of the 1920s and 1930s focused on how an individual could exist without losing their own sense of identity in a world where family, religion, and preserving the social order counted more than one’s personal and social life. Then the Second World War came and shook our social system to it foundations. The decades that followed turned our world upside down. We have never recovered to this day.

Between No South and Enduring South

Dixie

The Second World War was a watershed moment in the history of our people. Seventy years later, journalists and academics are still arguing over whether we are living in George Washington Cable’s “No South” or John Shelton Reed’s “Enduring South.” The truth is that we are living in both.

Before the mid-twentieth century, culture tended to be local and was generated by the interaction between the people and the land. Mass circulation newspapers, magazines, and the telegraph had been chipping away at that since the early 19th century. The rise of the modern mass media – radio, film, television, and finally the internet – introduced a third element and tilted the scale toward outside influences. It has made a global popular culture possible for the first time in history.

Globalization and modern telecommunications has opened debates about identity in all Western nations, not just the South. The French, for example, are just as concerned about losing their cultural identity as we are. The paradox of globalization is that it has increased the number of deracinated Westerners, but it has made identity a more pressing question than ever before. We live in an age of identity politics.

In this Age of Identity, cultural geographers have chartered the boundaries of an enduring Southern culture that owes more to geography, climate, history, demographics and migration patterns than to artificially drawn state lines.

Dixie Coalition

Southern culture is not homogeneous and contains regional variations on a common theme. Colin Woodard has labeled these clusters Deep South, Tidewater, Greater Appalachia, and New France. We no longer live in the South of hoop skirts, lynchings, or polio, but “Dixie” in some form is still very much with us. Perhaps now even more so than in the late 20th century.

Look at it this way: in the Sunbelt South, the bulldozer has a created a world in which we have gone from dirt roads to interstates, from the family farm to the suburbs, from the general store to Wal-Mart, from the Big House to the McMansion and from Waylon Jennings to Florida-Georgia Line. We still eat BBQ. We still enjoy football as much as before. We are still stung by mosquitoes, but we get our guns, ammo, and outdoor gear at Bass Pro Shops and Paula Deen teaches us how to cook.

We live in the age of Joel Osteen, Cracker Barrel, NASCAR, and Dollywood – a world that is still Southern, but which feels inauthentic. Yankees are still with us too. Instead of The Beverly Hillbillies and Lil’ Abner, we are treated to Honey Boo Boo and Swamp People. The old feeling of difference is still there whether the perspective is from the South or toward the South.

Largest Ancestry By County

According to the US Census, Dixie is still dominated by African-Americans and plain old “Americans,” who are Southerners whose ancestors have been here so long that they have lost touch with their British roots. Elsewhere, two centuries of European immigration has changed the ethnic mix of White Americans in the North and West and has the made the South more ethnically distinct than it was in 1860.

Southern English

Believe it or not, but the Southern accent still prevails across most of Dixie.

Christian Conservatives By County

H.L. Mencken coined the term “Bible Belt” in 1924.

Nearly a century later, self-identified Christian conservatives are concentrated in the South, unless you count Mormon Utah as Christian. As the North and West have grown more secular and liberal, the South has become more distinct as an enduring bastion of Christian conservatism. Religion has become more important to sustaining Southern identity as race has faded.

Conclusion

Core and Peripheral South

In 2015, Southern identity is stronger in some states than others, but there has always been a Core South and Peripheral South. Writing in 1935, Southern poet Allen Tate, one of the Vanderbilt Fugitives, defined the South this way: “it begins in the northeast with southern Maryland; it ends with eastern Texas; it includes to the north even a little of Missouri. But that the people in this vast expanse of country have enough in common to bind them in a single culture cannot be denied.”

American South

Anthony Smith, a British ethnographer and expert on nationalism, defines an ethnie as “units of population with common ancestry myths and historical memories, elements of shared culture, some link with a historic territory and some measure of solidarity, at least among their elites.”

In his 1997 book Power in the Blood, the Canadian writer John Bentley Mays traces his roots back to the South, and beautifully describes the Southern tradition as “noble, failed attempts to raise on Southern ground a culture rooted in the natural order of our seasons, to build a civilization free of cruel utopianism and metropolitan alienation, sustained by loyalties to place.”

In his 1862 essay, Southern Civilization; or, the Norman in America, J. Quitman Moore traced the origins of the conflict with the Yankee back to the English Civil War. He put it this way:

“Opposite under the banner of the king, stood the Cavalier – the builder, the social architect, the institutionalist, the conservator – the advocate of rational liberty and the supporter of authority, as against the licentiousness and morbid impulse of unregulated passion and unenlightened sentiment. No idealist, enthusiast or speculative system-builder, upheaving ancient landmarks and overthrowing venerable monuments; but a realist, a practical and enlightened utilitarian, bowing to the authority of experience and acknowledging the supremacy of ideas, forms and institutions that had received the hallowing sanction of time . An institutor by genius and a ruler by race, his pride was at once the sword of his most eminent virtues and greatest weaknesses, while honor was the touchstone of his character. Chivalrous in sentiment and magnanimous in deed, glory was his ambition, and loyalty the inspirer of his every thought, impulse and action. Elevated in his ideas and tolerant in his views, his selfishness was vicarious and his very faults wore the semblance of virtue. Unyielding in his principles, but compromising in his opinions, his conduct was governed more by sentiment than reflection, and more by association than either. Courtly in his manners and splendid in his tastes, a knightly generosity he practiced even toward his foes, and never lost his faculties in volumptuousness. Without being an abject advocate of passive obedience or a supporter of arbitrary power, he yet took ground against the revolutionary party, not as an enemy to liberal institutions or a well-regulated liberty: but, discovering in the doctrines and principles of the revolution a greater danger to the social and political system than from the alleged existing abuses, he preferred yielding his loyalty rather to institutions than abstractions, and felt it a duty to attempt to quench the lights of the incendiary philosophy, whose torch had been applied to the noblest monuments of civil wisdom yet erected by the genius of man.”

Even in its present highly degraded state, the dominant Anglo-Celtic ethnic core of Dixie and our Southern tradition still exists. It’s the ethnic and cultural glue that holds together these contiguous states as “the South.” If that ethnic core which was built up over three centuries is allowed to be displaced or its historical sense of solidarity is allowed to continue to disintegrate, “the South” will lose its coherence and whither away. We will become strangers in our own land.

That, my friends, is something we cannot allow to happen. Thank you.

If New England had left the Union in 1814, the U.S. would have turned out different.

Or if Virginia hadn’t relinquished its claims to the Ohio Country and the Old Northwest.

Or if George Washington had followed his apprehensions and not made a union with the Northern colonies/states.

After the battle of Manassas, a quick regroup of the Confederate Army should have occurred, followed by an attack from the North Side of Philadelphia. Then when Philadelphia was in custody. Launch a massive assault on Washington City. And keeping it under Confederate Control to which time Lord Byron’s would had to advocate to Lincoln terms of his surrender.

Confederates failed miserably every time they attempted to invade the North. They were not very good at offensive movements.

Guerilla warfare was the South’s forte. But their military leaders were educated at West Point, just like the Union officers.

To His Excellency, the President: Sir :

I have had the honor to receive your letter of the 3d instant, in which you call upon me, as the ” Commanding General, and as a party to all the conferences held by you on the 2ist and 23d of July, to say : ” Whether I obstructed the pursuit after the battle of Manassas. “Or have ever objected to an advance, or other active operations which it was feasible for the army to undertake.” To the first question I reply: No. The pursuit was “obstructed” by the enemy’s troops at Centreville, as I have stated in my official report. In that report I have also said why no advance was made upon the enemy’s capital (for reasons) as follows : The apparent freshness of the United States troops at Centreville, which checked our pursuit ; the strong forces occupying the works near Georgetown, Arlington and Alexandria ; the certainty, too, that General Patterson, if needed, would reach Washington with his army of more than 30,000, sooner than we could; and the condition and inadequate means of the army in ammunition, provision and transportation, prevented any serious thoughts of advancing against the Capital. To the second question, I reply, that it has never been feasible for the array to advance further than it has done— to the liue of Fairfax Courthouse, with its advanced posts at Upton’s, Munsou’s and Mason’s Hills. After a conference at Fairfax Courthouse with the three senior General officers, you announced it to be Impracticable to give this army the strength which those officers considered necessary to enable it to assume the offensive. Upon which, I drew it back, to its present position.

Most respectfully your obedient servant, J. E Johnston

Can you republish this article about Antifa? https://lumpkin.fetchyournews.com/2019/09/03/antlanta-antifascists-threaten-to-disrupt-american-patriot-rally-in-dahlonega/

Call me ASAP!!! I have a juicy story for you!

Westsylvania settlers, found out the hard way. with the whiskey rebellion, what the Feds can do.

It didn’t matter they fought the revolutionary war and were citizens of this new Union they helped build for the elite on the east coast.

The optics look similar today on how our veterans are treated.

There are some cultural and ethnic differences between Rebels and Yankees but they are not pronounced enough to draw a sharp distinction between the two. The unwholesome presence of the jew and the niggra have been the real source of our lack of national unity.

The Confederacy was not a White ethno-state though. The White planter elite wasn’t any better than today’s elites, and only cared about power and money not race.

https://bittersoutherner.com/from-the-southern-perspective/miscellany/what-you-dont-know-about-the-south

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2209873?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

https://www.counter-currents.com/2010/10/was-the-confederacy-a-tool-of-international-finance-1/

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/true-story-free-state-jones-180958111/

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Republic_of_Winston

http://www.alabamalegacy.org/free-state-winston/

https://www.amazon.com/South-Divided-Portraits-Dissent-Confederacy/dp/1581825870

Well, duh.

The White ethnostate is a concept that emerged in the 1970s.

Great use of maps.

There’s a brand-new review of a book that says antebellum industry in the South was bigger than they say. The book’s author limited his analysis to TX, MS, and AL because the book would have been impossible, maybe, if the entire South was considered, but two of those are core Southern states.

https://cwba.blogspot.com/2019/09/review-industrial-development-and.html?m=0

Thanks for the tip.

I will have to get that book!

Here’s the one that I currently have on the way:

https://www.amazon.com/Southern-Crucible-Making-American-Combined/dp/0199763607/ref=sr_1_2?keywords=southern+crucible+link&qid=1567642049&s=gateway&sr=8-2

I still prefer the term Southlander to Southerner or Southron because it has a more mythic and transcendent feel. However the Deep South is chock full of Negroes and their number is increasing not just by birthrate but a return to the South from the days in which they moved North to work in factories.That bodes ill for the White South. We will reach minority status long before the rest of the United States. Honestly I hate the climate. Its summers are hellish filled with 500 billion mosquitoes and every other kind of biting insect known to man and angry, vicious, and morbidly obese water moccasins.Driving at night in the South is so humid you have to use windshield wipers on clear starlight or moonlight nights and the insects are so think it sounds like rain hitting the car. Those who live here no whereof I speak! And I HATE New Orleans. It is so humid you can hardly breathe and the air is thick. Its like walking on the surface of cloud shrouded Venus. And Southern nights are never quiet. The buzzing of Cicadas can really reach insane levels that can blot out conversations.

@Hunter Wallace, the bottom line is in the future there won’t be a pure “White” race of people, or White ethno-states. The future will be admixtures and new races will emerge, because just like the rest of the natural world the human species continues to evolve and change. This is just a simple fact that cannot be denied. It doesn’t mean that European genetics will cease, but it does mean that “Whiteness” will inevitably cease to exist though. The vast majority of Whites simply do not identify as “White” as something to preserve anymore. This is why “White” Nationalism is a losing worldview and would be better served to fold up. I’m not saying I have a solution but I preferred to go the tribal anarchist route personally. I highly recommend the following video.

https://youtu.be/WBccuYTb_RE

In my view, liberalism is the cause of this situation, and anarchism is the most extreme form of liberalism. Thus, I don’t see how anarchism is a solution. It seems to be like tribalism and anarchism are a contradiction.

You totally missed my points. The bottom line is “Whiteness” will not exist in the future, and new races will come into existence. Also there are right wing strains of anarchism.

Whiteness will exist in the future. Non-whites will pass away.

http://hlmenckenclub.org/texts/anarcho-fascism-an-overview-of-right-wing-anarchist-thought-keith-preston

I recommend this article if you would look at it. Also the Appalachia region and the Wild West was Anarchist. Then you have the free state of Winston and Jones during the civil war are examples of Anarchist communities.

http://hlmenckenclub.org/texts/anarcho-fascism-an-overview-of-right-wing-anarchist-thought-keith-preston